The Air Squat

21/02/2022 # Coaching

The Air Squat

The squat, in the bottom position, is nature’s intended sitting posture (chairs are not part of our biological makeup), and the rise from the bottom to the stand is the biomechanically sound method by which we stand up. There is nothing contrived or artificial about this movement. The squat is essential to well-being. The squat can both significantly improve athleticism and keep hips, back, and knees sound and functioning in senior years. Not only is the squat not detrimental to the knees, but it is remarkably rehabilitative of cranky, damaged, or delicate knees. This is equally true of the hips and back.

We are going to discuss the Air Squat in little details today. The Air squat is a squat without any weight other than body weight. No movement is more foundational than the air squat. The functionality of the air squat is obvious anywhere we need to raise our center of gravity from a seated to a standing position (e.g., getting off the toilet, out of the car, off the couch).

Basic skeleton anatomy and muscular actions during Squats:

We are going to break the Air squat into 5 different phases, each phase can be classified into either static phase or dynamic phase of the movement. We will discuss points of performance to execute the movement in each phase, we will be using anatomical references and terminology to describe the movements. –

1) Starting Position

2) Descending position or Eccentric phase

3) Bottom Position

4) Ascending position or Concentric phase

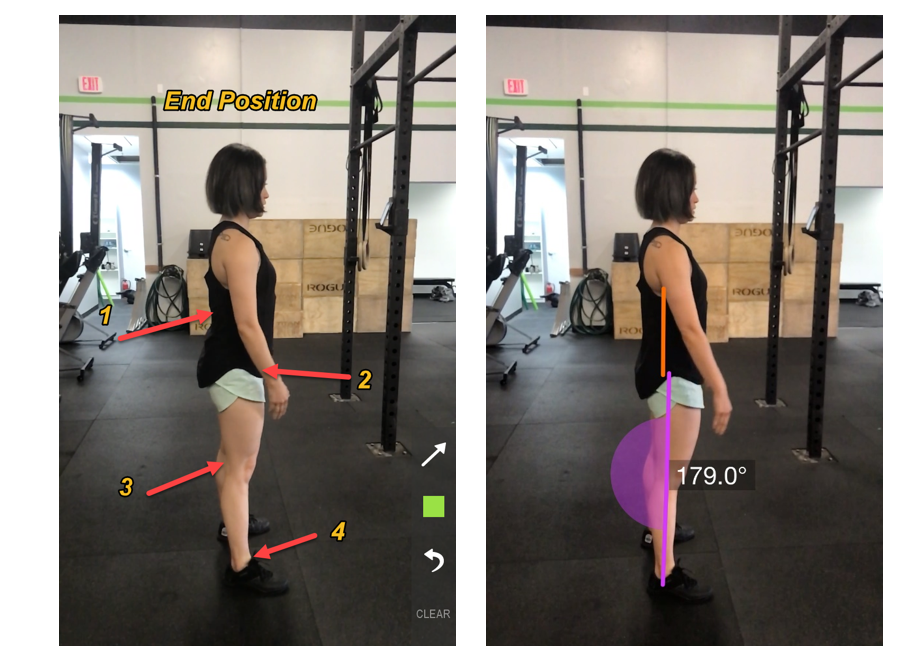

5) End Position

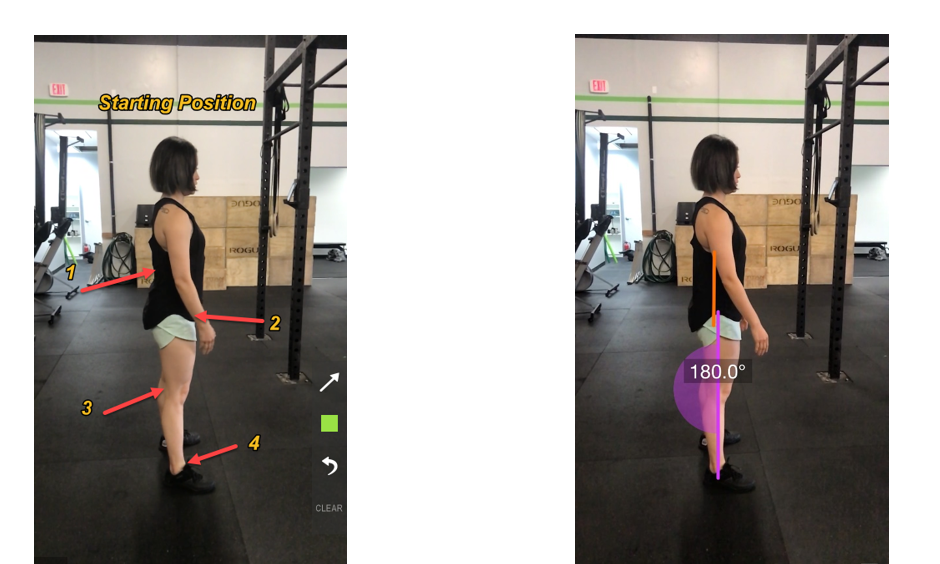

1) Starting Position:

The starting position for air squat is an upright standing position with a neutral (1) Spine (Sacroiliac Joint) to create stability around the core. The Coxal/Hip Joint (2), Tibiofemoral/ Knee Joint (3), and ankle (4) remain neutral, which is a full extension of the joints and looks close to a 180-degree angle deplanement on the sagittal plane. The stance is with the heels at shoulder width and the toes pointed out slightly.

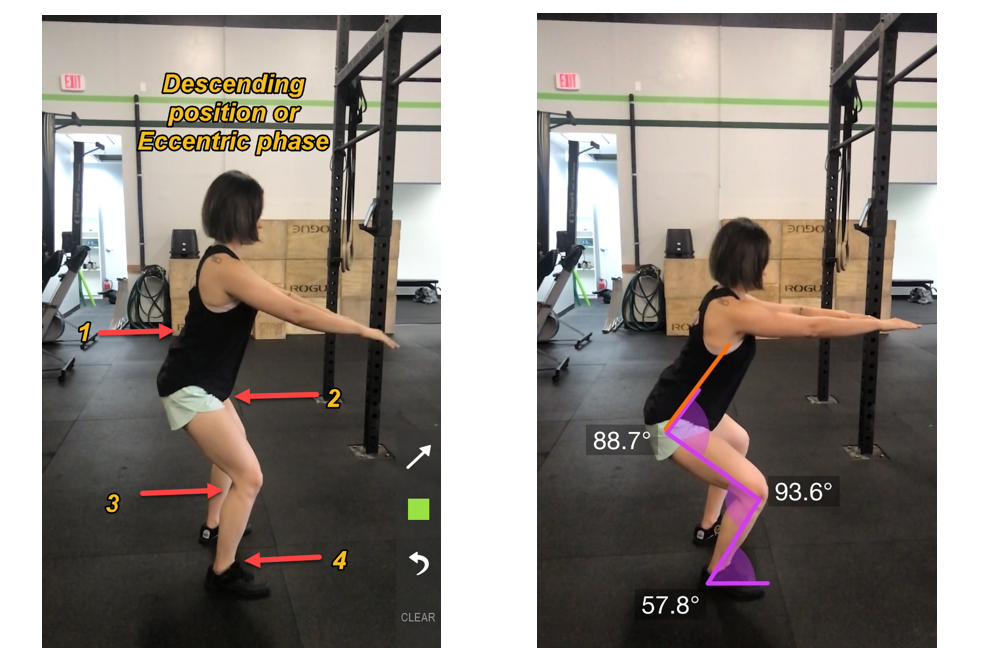

2) Descending position or Eccentric phase:

The descending portion of the squat starts with hip (2) flexion by pushing it back and down, resulting in knee (3) flexion to provide stabilization.

The hip flexors activate to control the descent of the weight and to assist the Spine (1) (vertebral column) in being in a natural position. The knee extensors and flexors both contract to allow for controlled descent of the body.

The hip extensors also contract to allow for increased stability of the back and hips. The weight of the body stays in the back part of the frontal plane by keeping weights on the heels, allowing us to engage the posterior chain of the body. The core muscles stay in isometric contraction (flexed) to increase stability and to protect the spine from injury.

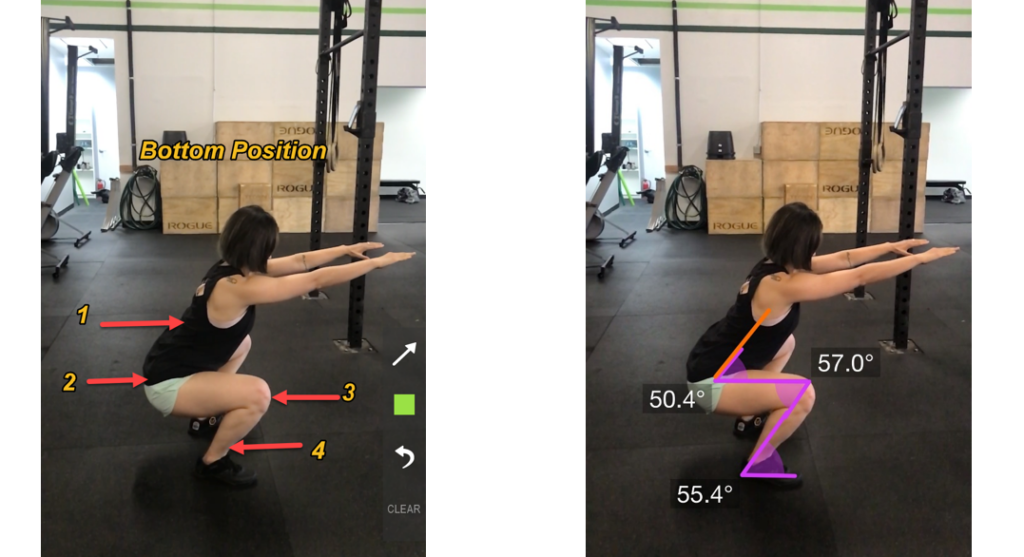

3) Bottom Position:

At the bottom position of the squat, the hip joint (2) is lower than the knees (3) as seen in the picture below. This forces the hip extensors to activate even more, as they are stretched, and allows them to provide more stabilization. The knee extensors, flexors, and hip flexors are also contracting to allow for a stable, seated position. Full range of motion is essential to sound squat mechanics. The core muscles stay in an isometric contraction to increase stability and to protect the spine from injury.

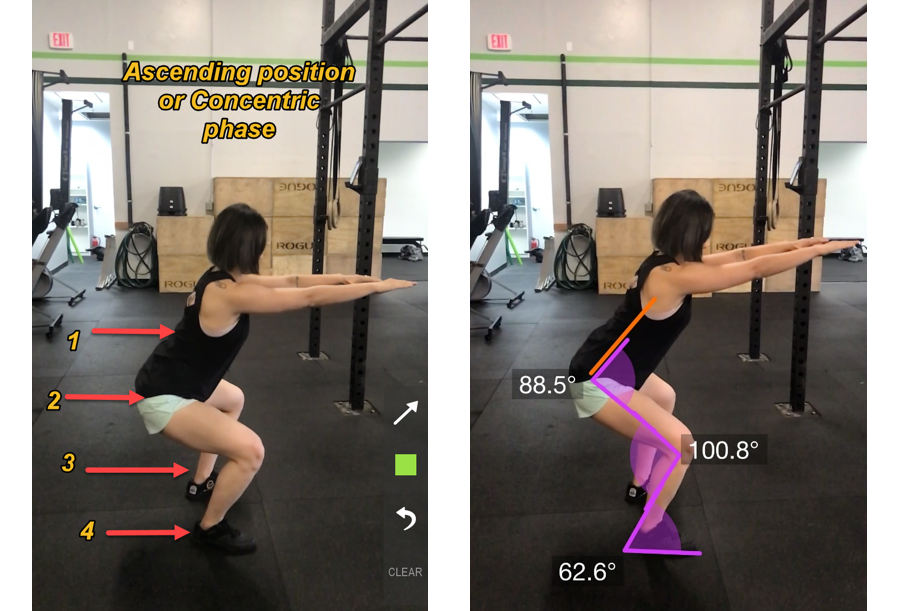

4) Ascending position or Concentric phase:

From the seated position or at the bottom of the squat position, we must overcome the force of gravity to push the bodyweight upward. The Ankle (4), Knee (3), and Hips(2) all start to extend at the same time so that the thigh can move out of the seated position, and we can begin to stand. The hip extensors also pull on the thighs to allow the hip and back to come to a more erect position. The core muscles stay in an isometric contraction to increase stability and to protect the spine from injury.

5) End Position:

The Starting and End position of an Air Squat is identical with a neutral (1) Spine to create stability around the core. Hips (2), Knee (3), and Ankle (4) joints remain neutral which is a full extension of the joints.

Conclusion:

No movement is more foundational than the air squat. Without proper squat, we are functioning at a fraction of our athletic capacity. Proper execution of squat requires proper points of performance which promote orthopedic safety, functionality, and mechanical advantage.

***Air Squat Points of Performance***

Midline stabilization

Maintaining a neutral spine demonstrates midline stabilization. This posture is critical to all functional movements, especially under load. Midline stabilization creates an unmoving, integrated trunk where the natural “S” curvature of the spine is wedded to the pelvis. A stable midline is maintained throughout the movement. This position is the safest posture for the back and provides a solid base to transmit forces.

Posterior chain engagement

Keeping weight in the heels during the squat demonstrates posterior chain engagement. This means incorporating the musculature on the backside of the body (hamstrings, glutes, erectors), which is necessary to maximize performance (e.g., load lifted, speed to completion). All of the pressure is not in the heels. The weight is distributed evenly from the balls of the feet to the heels.

Full range of motion

The full range of motion for the air squat is called “below parallel” (bottom position as shown in phase 3) to full extension of the Hips/ Knees (End Position as shown in phase 5 ). Below parallel is defined as the crease of the hip below the top of the knee. Full range of motion in our movements means taking the joints through their natural anatomical end ranges. This keeps the joints healthy and flexible, promotes the development of all the muscles surrounding the joint, and is often what life demands (e.g., getting off the floor).

Core to extremities

Core-to-extremity movements demonstrate a sequence of muscular contraction that begins with the large-force-producing, low-velocity muscles of the core (abdominals and spinal erectors) and hips and ends with the small-force-producing, high-velocity muscles of the extremities (e.g., biceps, calves, wrist flexors).

The squat is a core-initiated movement. First, the abdominals contract, and then the line of action is to press the hips back and down. The knees bend at the same time as the hips. Pressing the hips back helps activate the posterior chain muscles and keeps the balance on the frontal plane.

The above points of performance act as a framework for sound squatting movement. I like to call the framework a functional movement theme (ref-CrossFit Level 2 Training guide) to evaluate correct movement machines.

References:

Biel, A. (2014). Trail guide to the body, a hands-on guide to locating muscles, bones, and more. (5th ed.). Book of Discovery.

CrossFit Level 1 Training Guide Second Edition

CrossFit L2 Certificate Course Training Guide

Anatomy & Physiology – A Primer For CrossFit Trainers by Lon Kilgore, Phd

“Squat Clinic” from CrossFit Level 1 Training Guide – Second Edition, originally published in December 2002 at CrossFit.com Journal.

THE AIR SQUAT By CrossFit January 12, 2019